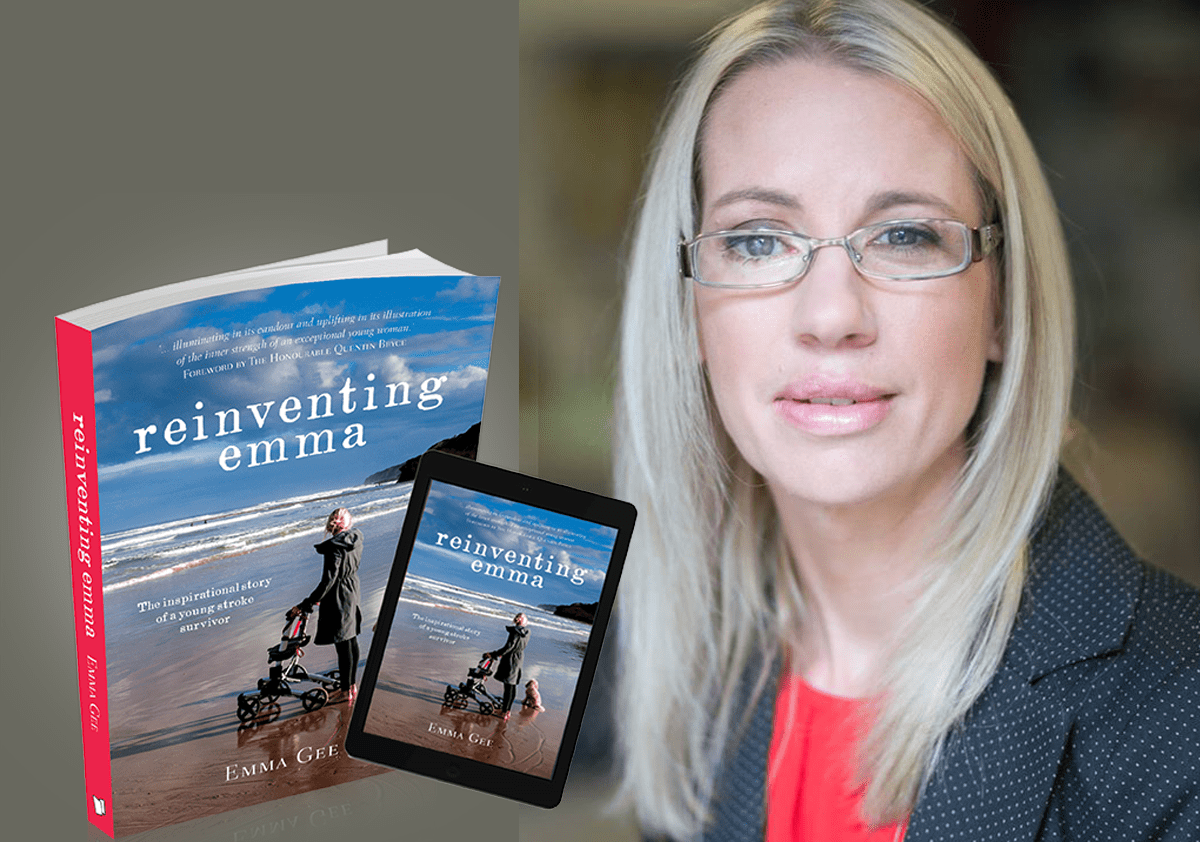

A Lived Experience of Stroke Rehabilitation Environments: Emma Gee

Emma Gee has been working as a co-researcher with the NOVELL Redesign project since its inception and brings a tremendous dedication and enthusiasm to all that she does. In the post below, Emma kindly shares some reflections on her involvement in NOVELL Redesign, and has put together some excerpts from her book, Reinventing Emma, that point to the importance of improving the rehabilitation built environment. Now working as an inspirational keynote speaker, workshop facilitator, consultant and mentor, you can find out more about Emma at her website: https://emma-gee.com

From Emma:

I was fortunate to be involved in the NOVELL Redesign Project. The NOVELL Redesign is a healthcare innovation project led by Professor Julie Bernhardt at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience & Mental Health. This project aims to establish an evidence-based platform for rethinking how stroke rehabilitation facilities are designed and integrated into new models of care.

The virtual workshops I attended enabled different stakeholders and end-users to rethink stroke rehabilitation in partnership with researchers and designers. We were able to explore four different topics and able to contribute our various expertise to brainstorm & design mock-ups of rehabilitation facilities that will be built in a virtual environment.

Selected excerpts from Reinventing Emma, iBooks:

“More time inside the rehab walls was going to destroy any remaining sanity I might have.”

“I felt as though I had been thrown into gaol. The nurse whipped off my shoes, threw up my bed’s sides and said, “Rest now, Dear. Dinner’s at 5pm and your buzzer’s here should you need anything. You’ll meet your therapists tomorrow.”

“After the hotel-like accommodation in the Sydney hospital, I was now forced to share a room with three other patients, strangers. Strangers who would be apparently returning soon, but I wasn’t particularly looking forward to meeting. All alone for the moment, I scanned the room through the thin blue nylon curtain that was my only privacy.”

“The furniture was cloned – same beds, same bedside tables, identical narrow chipboard lockers. At least I was next to the window, but the view was far from inspiring – a bleak car park and in the distance an industrial brick chimney. I felt abandoned in an alien world. Resigned, I collapsed back on the hard squeaky pillows. With no distractions, I felt forced to focus on my situation and all the things that were not right or fair about it. Endless negative issues circled in my damaged mind. I felt like I’d been dumped at Talbot’s doorstep, a complex machine with no manual. The discharge summary from Dalcross provided the new Talbot staff with a ‘problem list’. Now it was their job to write the manual.”

“At Talbot my days changed dramatically. In my Sydney hospital I had been allowed to stay in bed in my pyjamas and everyone did everything for me. My world was now controlled by the routine of the hospital. Each day started with a painful burst of light as Nurse Fran threw up the blind and wound up my bed, bringing my crooked prone body to a crooked seated position. Breakfast in bed, once a treat, was now a chore. I was given a shaving mirror to help me eat. It was embarrassing to admit that I’d even forgotten where my mouth was.”

“Talbot consisted of two different areas, the therapy area where I was to be ‘fixed’ and the ward where I would sleep or rest and wait in between”

“Speech therapy was held in a tiny shoebox of a room. It overlooked Talbot’s central garden courtyard but my view was of my eye-patched self. My wheelchair would be positioned by Nancy, my therapist, in front of a large mirror so I could track my facial movements.”

“Between sessions I was wheeled back across the glass bridge to the other side to rest. These sleep times to ‘rest and heal’ were far from restful. My roommates had visitors or the cleaners banged and crashed about. I’d lie awake, unable to move to toss and turn. I’d often head off to the next session feeling grumpy and irritable, and worried that I wouldn’t perform at my best.”

“I’d arrived at Talbot in mid-winter. By spring I was deemed medically fit enough to be able to propel my own wheelchair, which gave me a touch more freedom. In between sessions I’d exit the dark and gloomy life of the ward where my fellow patients were resting on their beds and wheel myself towards the ‘therapy zone’. Here, I’d park my wheelchair in the natural light and warmth of the glass walkway. If I positioned my chair at an angle, I could see the tin roof and treetops in the distance, a glimpse of the outside world while still safe behind the glass.”

“I decided it was time to book an appointment with the hospital hairdresser. She would come to us on the ward and temporarily occupy one of the storage rooms. I was hoping that the familiar soothing experience of having my hair washed would bring a little normality back into my life and boost my self-image”

“When my friends or family came unannounced to my therapy sessions I felt completely humiliated. Having them cheer from the sidelines while I stacked cones or threw quoits only made me feel disappointed for them that my recovery was so slow.”

“This made the Talbot cafeteria a good escape for me. Rather than sit in my room or join the other patients for their smokos, I would opt to sit among the buzz of the café. I’d order a lukewarm coffee, slurp it through a straw, and read Don’t Give Up-style motivational books, searching for a remedy for my low self-esteem and trying to face my latest fear – leaving Talbot.”